Uniformity of concepts and support for innovation: European Biotech Act

Publication date: February 2, 2026

Biotechnology has been included in the European Commission’s political programme for 2024–2029 as one of the key technologies for the EU’s economy and security.

The EU Biotech Act is an EU initiative aimes at making Europe a global leader in biotechnology by simplifying regulations, increasing funding (including €10 billion for innovation), and supporting bioproduction. The legislation covers innovation in medicine, agriculture, and industry.

The draft European Biotech Act introduces a new, coherent regulatory framework for the healthcare biotechnology sector in the European Union. Its main goals are to strengthen the EU’s competitiveness in the area of innovative healthcare technologies, accelerate clinical trials, and reduce the EU’s dependence on third countries such as the USA and China. Currently, EU regulatory processes are fragmented among member states, leading to differences in regulations even at the level of defining basic concepts, and sometimes even to their complete absence. The European Biotech Act aims to change this by introducing uniform definitions and procedures. In practice, this shortens administrative procedures and simplifies project and product classification while maintaining all safety requirements and regulatory standards.

Article 2 of the European Biotech Act serves a classic definitional purpose. Its primary goal is to standardize the legal terminology that defines the scope of the entire act. The definition of “biotechnology” provides the conceptual foundation for the remaining legal definitions contained in the bill. Biotechnology means the application of science and technology to living organisms, as well as to their parts, products, and models, for the purpose of modifying living or non-living materials for the purpose of generating knowledge, products, and services.

It should be noted that Polish law lacks a formal, general definition of biotechnology, which could previously lead to discrepancies in classification in administrative practice.

Unifying the concept of biotechnology at the EU level is of significant practical importance. It helps avoid situations where the same project would be considered in parallel by different administrative bodies due to the fact that it is partly classified as a medical product and partly as a food product. Such discrepancies further extended the time taken by the authorities to adjudicate.

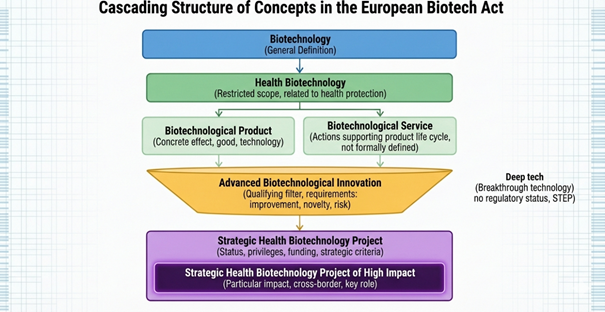

Biotechnology is a superior concept to others. This definition of health biotechnology was introduced, narrowing the general concept of biotechnology to applications directly or indirectly related to the protection of human health. This definition encompasses not only applications in medicine and pharmacy, but also biotechnological solutions related to animal health, plant health, veterinary public health, and food safety, provided that these areas contribute to the protection of human health. It is worth noting the reference to Article 168 TFEU in this definition, which serves as a limiting factor. It recalls the framework within which the Union has competence to intervene in the field of public health. It prevents the limits of EU competences from being exceeded. The definition of health biotechnology defines the material scope of the act and, to a certain extent, determines which projects may be eligible for support and procedures. It allows for a project to be clearly qualified for EU procedures already at the notification stage.

Within healthcare biotechnology, the Biotech Act distinguishes two cascading categories: biotechnological product and biotechnological service. It defines a biotechnological product as any good, technology, or activity resulting from the application of biotechnology, including any process, action, technique, tool, or knowledge related thereto. It is therefore a specific effect of biotechnological activity. The above clearly indicates that this definition is very broad. It should also be noted that this concept does not directly correspond to any category known to Polish law. While conceptually it may partially overlap with the categories of medicinal product or medical device, it is not identical to either.

However, the concept of “biotechnological service” has not been formally defined in the draft act and refers not to the result, but to activities supporting the product lifecycle. This concept appears primarily in the context of the “product lifecycle,” which allows us to conclude that a service should be understood as an element supporting the entire process of developing and implementing healthcare biotechnology products, rather than as a healthcare service in itself. The cascading nature of these definitions in relation to health biotechnology means that products and services refer only to activities supporting the development of the health biotechnology sector and do not cover other areas of health care.

Merely qualifying as a biotechnological product is only the starting point. For a project to be eligible for the support mechanisms provided for in the act, it must demonstrate the characteristics of an advanced biotechnological innovation. This definition establishes a set of material conditions that must be met cumulatively, with alternatives being permitted within each condition. Above all, the innovation must, based on preliminary scientific or technical evidence, demonstrate real potential for achieving significant improvements over existing solutions in terms of effectiveness, safety, sustainability, accessibility, and/or cost-effectiveness. At the same time, as the definition implies, due to its novelty, technical complexity, or potential to create new markets, it involves a high level of technological or commercial risk and is capable of creating new markets or significantly transforming existing markets. In the draft act, this concept serves primarily a regulatory and qualifying function, not a separate legal status. Fulfilling and demonstrating these conditions allows for further assessment. Article 32 explicitly refers to Article 3, which specifies the conditions for designating a project as strategic. This structure indicates that meeting all of the above criteria for “advanced innovation” is a logical and legal intermediate step. It serves as a “filter” that a project must pass to even apply for higher status. Designating a project as an advanced biotechnological innovation offers several benefits. According to the draft act, initial support, including regulatory advice, is provided for small and medium-sized enterprises that can document compliance with these criteria. This support is intended to help companies develop their project and qualify it as “strategic.”

At this stage of the analysis, it is necessary to address the concept of deep tech which appears only fragmentarily in the draft act. According to the definition, deep tech refers to innovation with the potential to deliver transformative solutions, based on breakthrough achievements in science, technology, and engineering. Designating a project as deep tech does not grant it a separate regulatory status, nor is it a step in the procedure for recognizing a project as strategic. It merely allows for additional qualification for access to existing EU funding mechanisms. Simply put, deep tech is not a new concept; its twin definition can be found in Regulation 2024/796 on the establishment of a Strategic Technologies Platform for Europe (hereinafter referred to as STEP). In the STEP Regulation, deep tech is known as “deep technology.”

The term “strategic” refers to the concept of a strategic health biotechnology project. This term appears only in the context of the procedures for recognizing a project as strategic. Such a project must meet specific criteria, including strengthening value chains and industrial capacities in the health biotechnology sector, developing research and technological infrastructure, accelerating the implementation of innovations, supporting education and talent development, and increasing the EU’s preparedness for health threats. Strategic status grants the project specific administrative privileges and access to public funding, and also allows the use of accelerated EU procedures. It is worth noting that in the draft act, this term is not included in the definitions section; its meaning is clearly defined in the text of the regulations, indicating that the legislator treats it as a contextual concept, linked to procedures and powers, rather than merely descriptive.

An extension of this category is the high-impact strategic health biotechnology project. These projects have a particularly significant impact on the EU biotechnology ecosystem. They can be cross-border, serve as a catalyst for other projects, and play a key role in accelerating innovation implementation. Every high-impact strategic project is also a strategic project, and both types of projects rely on advanced biotechnological innovations, creating a cascading structure of dependencies. This is presented as follows:

As a result, the concept of advanced biotechnology innovation plays a preparatory and structuring role in the act, allowing for the identification of projects with high innovation potential before they are formally recognised as strategic, while the concepts of strategic project and high-impact strategic health biotechnology project are used to formally grant administrative status and powers in the EU, which has significant practical implications for project implementation and access to financial support and accelerated procedures.

Continuing the analysis of key concepts in the European Biotech Act, we should focus on bioproduction (bioprocessing), which is often used in conjunction with biotechnology in the draft act. Therefore, these two concepts should be distinguished from each other. Based on the definition itself, bioproduction should be understood as the next phase in the context of a biotechnological product. Biotechnology is the domain of discovery, conception, and the development stage, while bioproduction is the commercialization phase, the production of a finished product. This is the moment when a biotechnological product or service is transformed into a finished, repeatable, and marketable product. As with biotechnological products, projects in this phase can count on accelerated and simplified administrative procedures and easier access to investment financing programs.

The definitions described above indicate what the EU supports; the next definition introduced is different in nature, focusing on the method. We are talking about biotechnology clusters. The draft act assigns clusters several key functions. Primarily, they bring together interconnected companies, research institutions, and organizations focused on biotechnology, while simultaneously fostering collaboration and innovation. This makes clusters an ideal environment for project development. An analysis of Article 15 of the draft reveals their further role: they are not merely places where various organizations gather. The EU sees them as a key tool for building strong networks. Article 15 explicitly states that the Commission and member states must promote cooperation and networking between clusters, especially those from different regions and countries. In practice, this means that clusters must cooperate with each other.

After outlining the general subject matter of the act and the way biotechnology is understood by the EU project, it is necessary to move on to the analysis of definitions relating to entities participating in the implementation of the objectives of the regulation.

It’s best to begin the analysis with the definition of “project promoter”. This definition is quite broad; a promoter can be either a company or a consortium of companies. This concept was introduced to clearly identify the entity responsible for implementing strategic projects in the field of health biotechnology. Beyond responsibility itself, it also facilitates operational and coordination between the “union” and the company. However, the draft regulation does not treat all potential promoters uniformly. This leads to the identification of a specific category of entities: small and medium-sized enterprises (hereinafter referred to as SMEs).

Let us begin with the concept of an SME. It is certainly not a new concept, so the draft act refers only to Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC, dated May 6, 2003. The Biotech Act provides for special treatment for SMEs, as well as start-ups and scal-ups, often lumped together. This privileged approach facilitates and prioritizes access to EU support mechanisms. This is evident in administrative support, access to financing, participation in clusters, and the use of strategic project resources. This regulated position of SMEs, start-ups, and scal-ups allows for a level playing field, based on the smaller or limited resources available to these entities.

On the financial level, the Biotech Act leverages existing EU and national financing mechanisms to increase investment in the health biotechnology sector. The European Investment Bank Group (hereinafter: EIBG) plays a key role in this regard, supporting the mobilization of public and private capital through the use of EU investment instruments, particularly the InvestEU program. The EIBG participates in the development and implementation of instruments such as the EU Health Biotechnology Investment Pilot, which aims to leverage additional financial resources, including private capital, and reduce the investment gap in the sector.

In parallel, implementing partners operate the InvestEU financial instruments operationally, leveraging EU guarantees, equity and debt instruments, and advisory support to stimulate investment in biotechnology companies and projects. This group includes, in particular, the European Investment Bank and the European Investment Fund, as well as instruments such as HERA Invest, which strengthen the financing of healthcare biotechnology.

The definitions defining the scope and entities of the Act have been discussed above. Now, let us focus on another definition, which aims to streamline the entire permitting process. Deriving directly from the definition, this process encompasses all relevant permits for the construction, expansion, transformation, and operation of strategic medical biotechnology projects and strategic high-impact medical biotechnology projects, including building permits and environmental impact assessments and permits, if required. It also encompasses all applications and procedures from confirmation that the application for such permits is complete to notification of the decision on the outcome of the procedure by the relevant single point of contact. To ensure efficiency and predictability, the entire process from confirmation of the application’s completeness cannot exceed 10 months for strategic health biotechnology projects and 8 months for strategic high-impact projects. Only one limited extension of up to 3 months is permitted in exceptional, justified cases. For balance, the time required to prepare the environmental impact report has been excluded from this deadline. Additionally, the regulation provides for the establishment of “single points of contact” in each country. Within 45 days, such a point conducts an initial verification of the application’s completeness, which can accelerate the subsequent process of submitting applications for further completion by the authorities. Furthermore, the single point of contact is responsible for further coordination of the procedure between the project promoter and the authorities. These new mechanisms are intended to make the procedure transparent and streamlined.

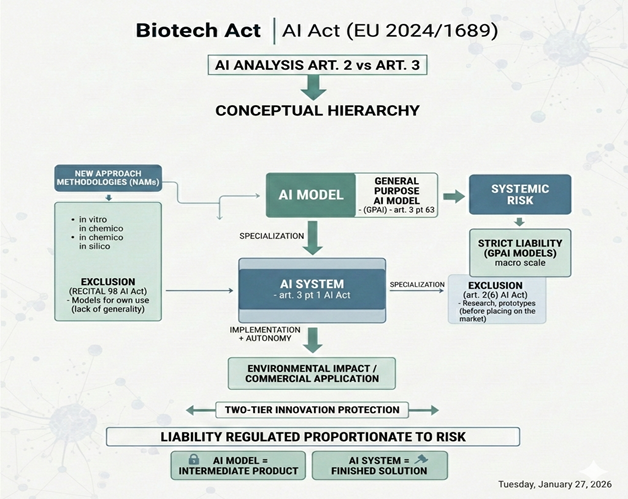

In the analyzed fragment, the Biotech Act, in addition to introducing new terms, also uses definitions already established in other EU regulations. Terms such as AI system, general-purpose AI model, clinical trial, or advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) are not established in this act as new, autonomous legal definitions.

An analysis of Article 2 of the Biotech Act in conjunction with Article 3 of Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (hereinafter: AI Act) reveals a precise conceptual hierarchy in which the distinction between an AI model and an AI system is fundamental. The EU legislator does not introduce an autonomous legal definition of “AI model.” Instead, in Article 3(3) of the AI Act, it defines only a “general-purpose AI model” (hereinafter: GPAI), which has significant consequences for the interpretation of the status of research tools. The lack of a general definition of an AI model means that an AI model itself does not constitute an independent subject of regulation until it is implemented within an AI system (Article 3(1) of the AI Act) or reaches the parameters of the GPAI model. How, then, does the EU legislator define GPAI? Article 3(63) defines a general-purpose AI model as an advanced technological component acting as a highly specialized intermediate product. This model is characterized by being trained on a large amount of diverse data using large-scale self-monitoring techniques, allowing it to independently identify patterns and correlations without direct human supervision. To be considered a general-purpose model, it must demonstrate significant generality, understood as universality and the ability to operate in multiple contexts. Here, it is important to distinguish two key exemption mechanisms that protect innovation in biotechnology. First, according to Recital 98 of the AI Act, models trained for specific, narrow tasks are excluded from the definition of GPAI due to their failure to meet the generality requirement. Second, Article 2(6) of the AI Act introduces an exemption for GPAI used for research, prototyping, and pre-market prototyping activities. Therefore, while Recital 98 protects a model based on what it is (or rather, what it is not), Article 2(6) of the AI Act protects it based on where it is located and what it is used for. This two-level protection provides a secure foundation for the development of New Approaches (hereinafter: NAMs). It should be noted that NAMs are a broad research category, encompassing in vitro methods (based on cells or tissues), in chemico methods (based on chemical substances), and their combinations. However, in the context of the AI Act, in silico methods, i.e., advanced computer simulations, are crucial. Contemporary in silico approaches increasingly integrate AI/ML technologies. This application is confirmed by the European Medicines Agency’s Reflection Paper on the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Medicinal Product Lifecycle, which highlights the potential of computational approaches in replacing, reducing, and refining animal testing. This protection lasts as long as the model serves as a raw analytical component within the laboratory. The critical moment for the researcher is the transition from model to AI system, which occurs when the algorithm is integrated with the application layer and granted a certain level of autonomy. Such conclusions can be drawn based on Recital 97 of the AI Act, in which the EU legislator clarifies that general-purpose AI models constitute only a component of AI systems and require the addition of additional elements, such as a user interface. Furthermore, pursuant to Article 3(1) of the AI Act (definition of an AI system), the system is defined by its autonomy and ability to influence the environment, which is excluded in the phase of applying NAM methods under Article 2(6) of the AI Act. Only when the model’s intended use changes from research to commercial does the legal definition of an AI system become satisfied, which entails the full scope of obligations under the AI Act.

In summary, the distinction between an AI model and an AI system serves a structuring function in the EU legal architecture. Recognizing a model as a “semi-finished product” and a system as a “ready-made solution” allows for precise targeting of obligations to the appropriate entities. Thanks to this dichotomy, legal rigor does not paralyze innovation at the stage of creating raw algorithms (e.g., within NAMs), but rather activates proportionally to the risk generated by a specific, autonomous application of the system in the real world.

However, an important caveat should be made: while narrowly specialized models (using broad exemptions) dominate in specific biotechnological applications, the AI Act generally imposes strict liability on the models themselves if they are classified as GPAI models posing systemic risk. In such a case, due to their enormous scale and potential, the legislator imposes obligations on their providers that go beyond the standard regime for “intermediate products.” Thus, although the model in NAMs remains “safe,” on a macro scale, the EU legislator protects itself against the risks stemming from the most powerful technological foundations before they are implemented as specific systems.

The Biotech Act also introduces significant changes related to the concept of clinical trials, as defined in Regulation 536/2014 (CTR). These changes are intended to simplify and accelerate clinical trial procedures. The authorization period for multinational trials will be shortened from 106 to 75 days, including ethical review. For trials in which medicinal products are used in accordance with the marketing authorization, a definition of “minimal-intervention clinical trial” has been introduced. In such cases, additional diagnostic products pose minimal risk, and the review will essentially be limited to ethical review, which contributes to reducing bureaucracy.

Visible changes are also anticipated in the context of advanced therapeutic therapies (hereinafter: ATMPs). Due to the dynamic development of gene and cell therapies, and tissue engineering, which has outpaced the literal wording of existing definitions, it was deemed necessary to clarify these concepts. To this end, the Biotech Act explicitly authorizes the European Commission to adopt delegated acts and clarify the definitions of gene therapy medicinal products, somatic cell therapy medicinal products, and tissue engineered products, without simultaneously expanding the scope of ATMPs. Procedural simplifications for ATMP developers are particularly important, especially those that involve or contain genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The Biotech Act introduces a risk-proportionate approach, recognizing that for specific, precisely defined categories of advanced research therapies—such as non-replicative viral vectors —the risk to human health and the environment is, in practice, zero or negligible. As a result, the obligation to conduct a full Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) has been abolished and replaced by a reasoned declaration by the sponsor explaining why the product falls into the low-risk category, with this declaration being subject to review by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use.

In addition to the simplifications and accelerations provided for in the Biotech Act, it introduces mechanisms to prevent biotechnological abuse. The central concept is biological threat, defined as risks posed by harmful biological agents, such as pathogens or toxins, capable of causing disease or significant social consequences, regardless of their origin. The definition encompasses both natural, accidental, and intentional threats. Biological threat is thus a superior concept, with other definitions serving a instrumental function. Against this backdrop, the legislator distinguishes biodefense from biosecurity, giving them complementary but not identical meanings. Biodefense encompasses actions, policies, and measures – particularly those undertaken by states—that aim to prevent, protect, and peacefully counter biological threats. This encompasses the full cycle of biothreat management: from preparation and early detection, through assessment and response, to post-incident recovery. Biological defence is therefore of a strategic and institutional nature, closely linked to public security, health protection and the resilience of states and the Union as a whole, which is reflected in the mechanism for recognising projects with a high impact on the Union’s defence capabilities in the area of biotechnology.

Biosecurity, on the other hand, is explicitly defined in the Biotech Act as the protection, control, and accountability of high-value biological agents, technologies, materials, and toxins, as well as critical information related to them, against unauthorized access, loss, theft, misuse, diversion, or intentional release. This definition is horizontal and preventative, aimed at mitigating risk before it occurs.

Unlike biodefense, which focuses on the ability to respond to biological threats, biosecurity serves as a preventive mechanism, implemented through uniform supervisory instruments across the EU, such as screening for legitimate need, identifying and monitoring suspicious transactions, and classifying a limited category of “biotechnology product of concern”. In this sense, biosecurity addresses the question of how to systemically mitigate the possibility of a biological threat before it becomes the subject of biodefense activities. Biotechnology products of concern are linked to the concept of biosecurity. The EU proposal introduces a legal definition of this concept. It encompasses all goods, services, or technologies, including software resulting from the application of science and technology to living organisms, their parts, products, or models, provided they demonstrate significant potential for biological misuse and are enumerated in Annex I to the regulation, along with any quantitative programs or exemptions. This definition serves as a regulatory gateway: only the classification of a product as a “biotechnology product of concern” triggers a specific biosecurity regime, encompassing verification, documentation, and reporting obligations. At the same time, the act provides for a flexibility mechanism, i.e., the possibility of updating Annex I through delegated acts. Additionally, a specific subcategory of products of concern is listed: devices enabling the synthesis of nucleic acids in laboratory conditions. Due to their potential to produce sequences of concern outside of centralized control systems, the Biotech Act requires them to be equipped with automated systems to verify the synthesised sequences against sequences of concern.

An integral element of this framework is the concept of “legitimate need”, which serves as a normative filter separating permitted use of technology from potential misuse. Legitimate need refers to the need for a given biotechnology product for legitimate, peaceful, and scientifically justified purposes, such as research, production, breeding, experimentation, storage, internal transport, or destruction, provided that these activities are undertaken by a legitimate member of the scientific community or a legally operating company, in compliance with applicable international treaties, laws, and regulatory standards. Against this backdrop, the Biotech Act introduces a specific and directly applicable obligation on entities making biotechnology products of concern available on the EU market, including through online platforms. These entities are required, for each transaction, to verify the identity of the purchaser, record the transaction, and actively assess the existence of a “legitimate need.”

The biosafety regime covers any situation in which an entity gains access to technology, as the concept of “making available” in the Biotech Act encompasses any provision of a product, whether for consideration or not, both within and outside the EU. This means that control obligations arise at the stage of granting access to the technology, not only in connection with its actual use. At the same time, the Biotech Act allows for the testing of products, including GMOs, within regulatory sandboxes, where making available takes place under strict supervision and is not considered as placing on the market.

The concepts presented above encompass the full spectrum of definitions introduced or used by the European Biotech Act and demonstrate that the definitional section of the act was designed systematically and purposefully. These definitions are not merely for organizational purposes, but rather establish a framework for the application of the entire regulation: they define the scope of the act, the sequence of procedures, and the point at which specific support or control mechanisms are triggered. Their cascading structure allows for gradual differentiation of the legal status of projects and entities, depending on the stage of technological development, level of innovation, and potential risk.